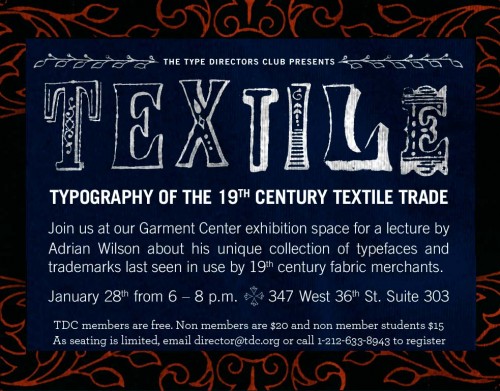

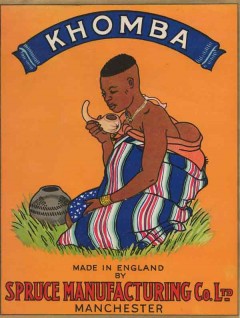

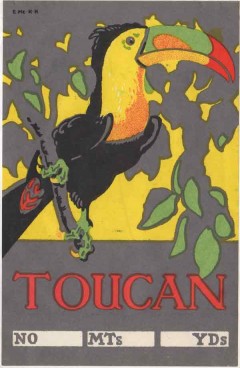

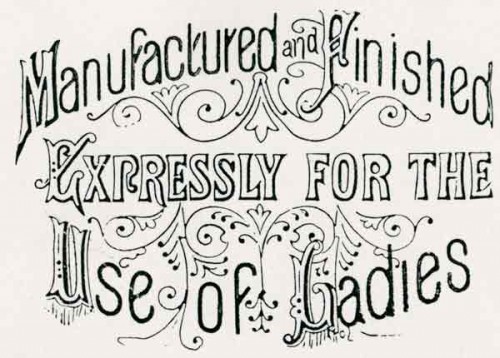

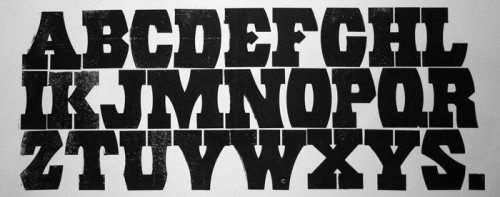

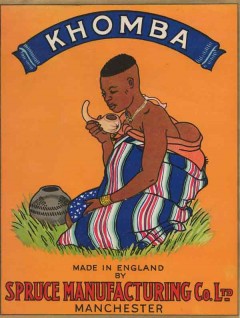

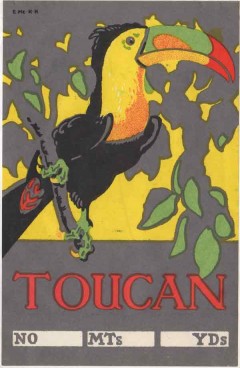

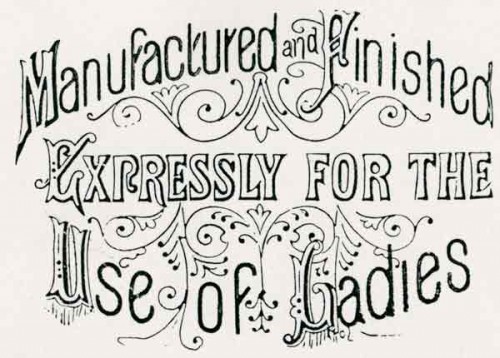

One week from today, the Type Directors Club in New York will host a lecture by Adrian Wilson about his collection of ephemeral lettering artifacts from the English textile trade of the 1800s and early 1900s. Wilson was kind enough to provide me with some sample images (below) and an interesting PDF describing the collection.

The topic of fabric merchant labels is an obscure one, but there seem to be many parallels with similarly intriguing fruit crate labels from roughly the same period. The text from the PDF gives some background on what Wilson will be discussing…

The 1842 Design and Copyright Act required that all pieces of cloth had to be clearly stamped of labeled with a “faceplate” that included the supplier’s identifying mark, and the cloth’s type and length.

Wilson’s collection — which he salvaged from cotton warehouses in Manchester, England — includes “over 2,000 hand-made wood and copper stamps used for printing the marks, around 4,000 unpublished printed stamp designs, and around 800 paper shippers’ tickets”. He was a guest on BBC’s Antiques Roadshow in 2005, but the collection has still yet to be shown publicly at any significant level.

Even after seeing all the background info and sample images, I’m still not 100% sure what to expect from the lecture. I am pretty confident, though, that it will include a lot of ornamented 19th-century lettering; and that’s enough for me.

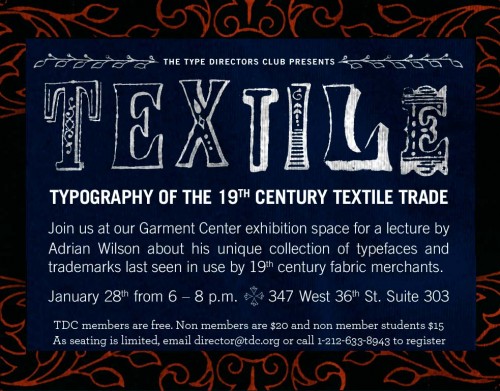

What: TEXTile, a lecture about the typography of the 19th century textile trade

When: January 28, 2010; 6–8 PM

Where: Type Directors Club; 347 W 36th St, #603; New York, NY [map]

Cost: Free for TDC members; $20 for non-members; $15 for students

Registration: E-mail director@tdc.org or call 212-633-8943

19th century textile trade ephemera courtesy of Adrian Wilson

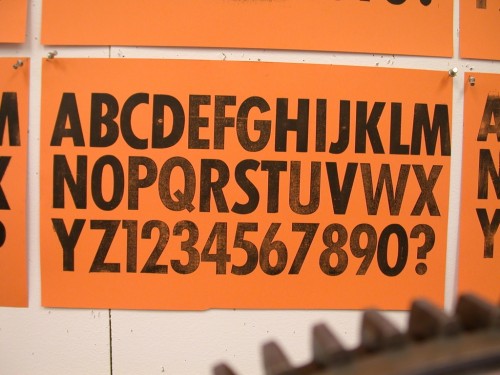

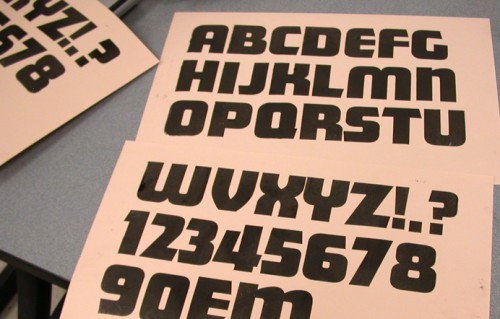

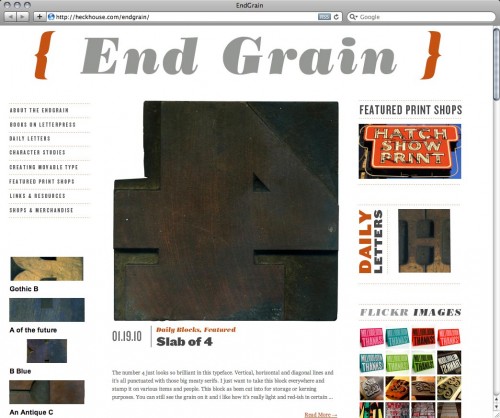

A portion of Bethany Heck's wood type collection

Bethany Heck is a student currently in her senior year in the Graphic Design program at Auburn University in Alabama. She has been collecting wood type since her freshman year there — a fact that seems to make sense considering her design pedigree (her father teaches graphic design). To date, she estimates her collection at about 600 wood type blocks — some as part of complete fonts and some as miscellaneous sorts.

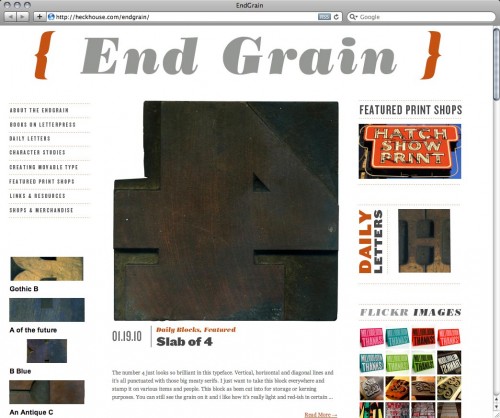

End Grain is Bethany’s new website which showcases her collection, as well as other letterpress-related content. She describes its inception thus…

The End Grain was born out of my desire to have some sort of letterpress website […] I was frustrated by the lack of sites dedicated to letterpress and I wanted a place I could go and just get lots of great examples of letterpressed works and hear from others who shared my passion for wood type.

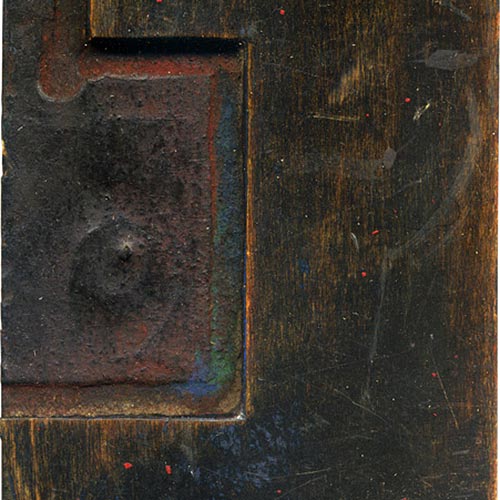

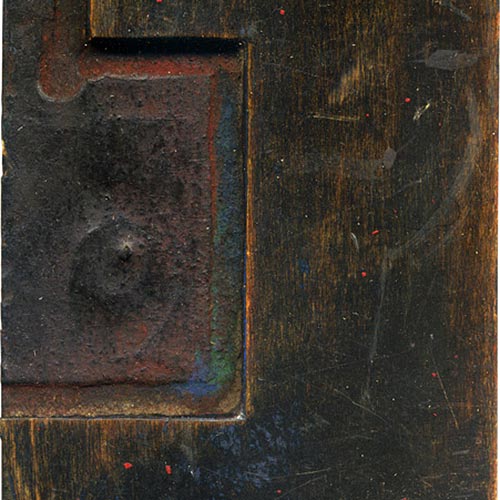

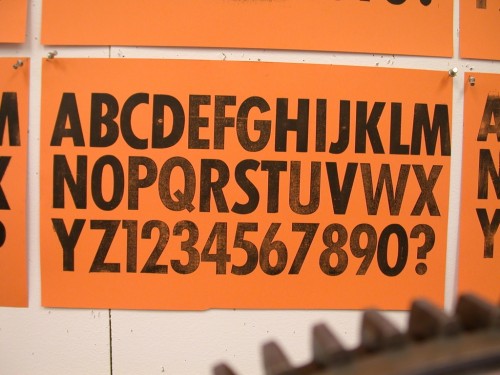

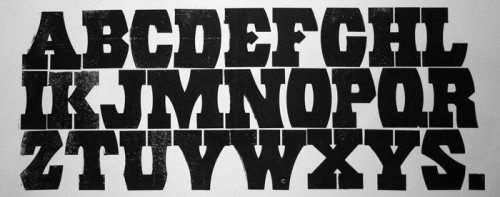

I have been advising Bethany with some of her work on the site so far, which includes several distinct features. First, the Daily Letters and Character Studies series of posts highlight Bethany’s growing collection of type, piece by piece. She provides historical details about the typefaces and manufacturers, but the most prominent and interesting aspect of the write-ups is her attention to the details of each particular block as its own unique object. Her reflections on specific scratch marks, manufacturing irregularities, specks of dried ink, etc often border on archaeological examinations. The posts are appropriately accompanied by high-resolution scans to show all the details.

Details from wood type scans at End Grain

Some blocks are also presented side-by-side with their prints for comparison. The prints aren’t necessarily the cleanest proofs possible, but this is partially forgivable considering the limitations of Bethany’s on-press experience so far.

Beyond showing Bethany’s type collection, the site functions as a resource for others interested in letterpress printing, with growing reference info on print shops, websites, retail stores, etc. Relevant content is also aggregated from sites like Flickr, Etsy, eBay, and Twitter.

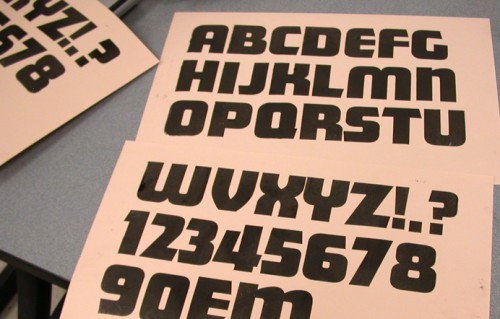

Another element of interest on End Grain is a series of posts documenting Bethany’s experiments with movable type production. The projects so far have ranged in scope from replacing missing characters in an incomplete font, to creating blocks of a digital typeface that hadn’t previously been available as movable type.

Up until now, all of the projects have been executed by affixing thin laser-cut plexiglass to a wooden base, emulating the veneer type production process.

Plexiglass veneer cuts and wooden base blocks for a set of Futura Condensed printing type. Note the guidelines inscribed on the base blocks to assist in aligninment when affixing the veneer cuts.

Futura Condensed with plexiglass veneer replacement blocks

Print made with the completed Futura Condensed font

Replica blocks of № 504 made with clear plexiglass

Print made with replica blocks of № 504

Plexiglass veneer blocks of Matinee Gothic

Print made with the Matinee Gothic blocks

These projects on their own are enough to warrant recognition, but the fact that they’re all done by the same student and presented the way they are makes them that much more notable. Furthermore, knowing that Bethany’s printing experience has been relatively limited, it’s impressive that she’s enthusiastic enough to initiate her own projects. This comes as no surprise though, knowing her strong personality and enthusiasm. It’ll be interesting to see what other things she does in the future and beyond graduation.

Image courtesy of Tillamook Air Museum

While driving up the West Coast last summer, I passed what is probably the largest example of typography that I have ever seen. Off Pacific Coast Highway 101, the blimp hangar at the Tillamook Air Museum stands 192 feet tall, and is reportedly the world’s largest clear-span wooden structure.

Photo from TheRogue on Flickr

Emblazoned on the side of the hangar are the words AIR MUSEUM, set huge in what appears to be Helvetica Bold (or is that Helvetica Neue Medium?) — easily legible from thousands of feet away.

After seeing the hangar and making my own estimates, I confirmed with the museum’s curator, Christian Gurling, that the glyphs measure 100 feet from baseline to cap-height. That’s ≈120,000 pt Helvetica!*

Depiction of the scale of the Tillamook Air Museum letters relative to a 6-foot tall person

Christian also told me that 500 gallons of paint were used for the job, which was done in the summer of 1994. Unfortunately, he didn’t have any details about how the letters were applied. I’m guessing they were enlarged by superimposition on a scaled grid, outlined, and then filled in (not everyone can hand-paint Helvetica from memory, after all). I only saw the hangar from afar, but I’d guess a closer inspection of the letters would reveal more clues.

Larger typographic lettering may exist somewhere else in the world — most likely as part of an air traffic guidance system, if so — but I’ve yet to see it in person. Feel free to cite any relevant examples in the comments.