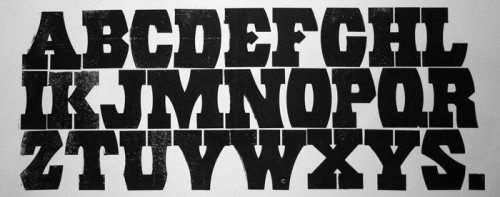

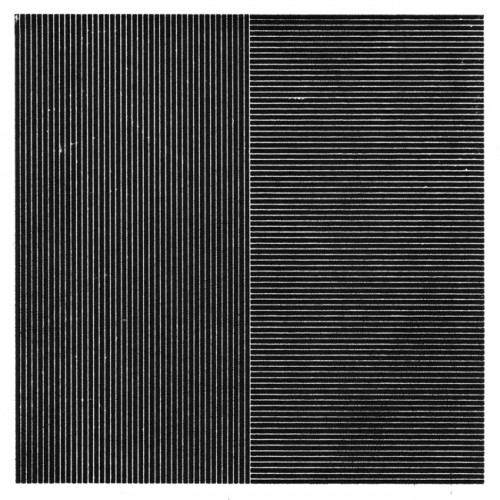

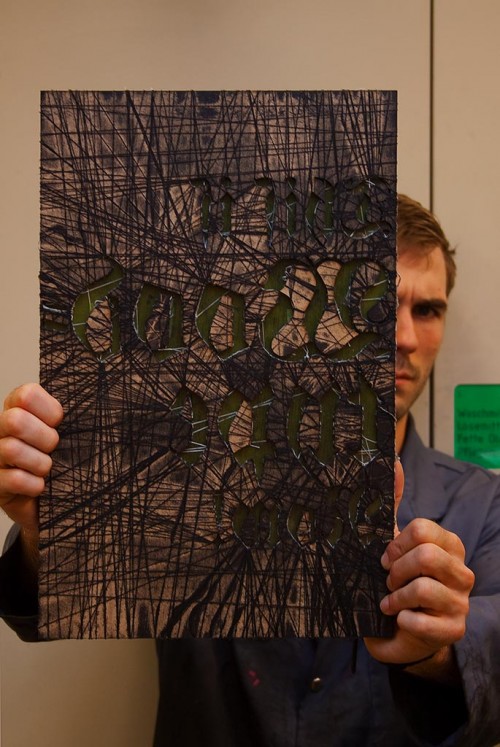

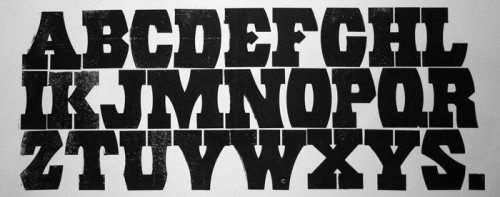

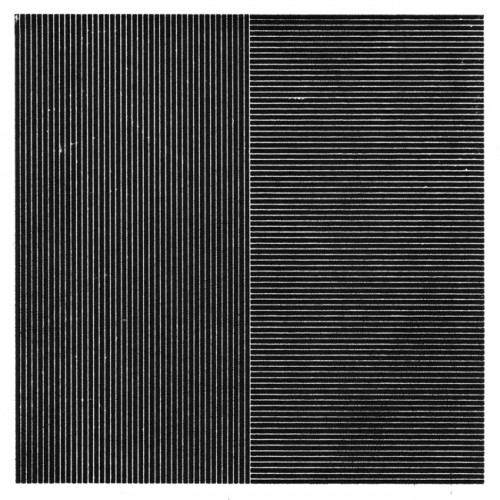

A portion of Bethany Heck's wood type collection

Bethany Heck is a student currently in her senior year in the Graphic Design program at Auburn University in Alabama. She has been collecting wood type since her freshman year there — a fact that seems to make sense considering her design pedigree (her father teaches graphic design). To date, she estimates her collection at about 600 wood type blocks — some as part of complete fonts and some as miscellaneous sorts.

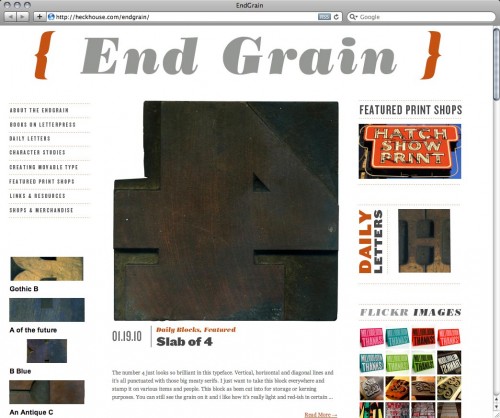

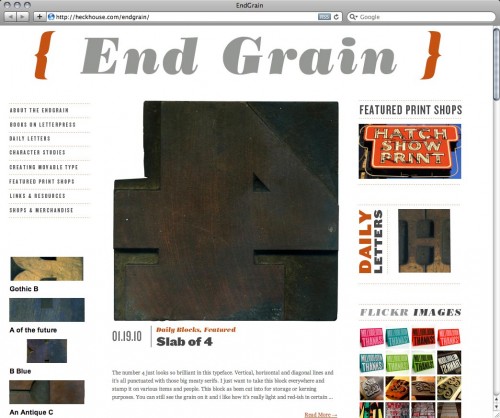

End Grain is Bethany’s new website which showcases her collection, as well as other letterpress-related content. She describes its inception thus…

The End Grain was born out of my desire to have some sort of letterpress website […] I was frustrated by the lack of sites dedicated to letterpress and I wanted a place I could go and just get lots of great examples of letterpressed works and hear from others who shared my passion for wood type.

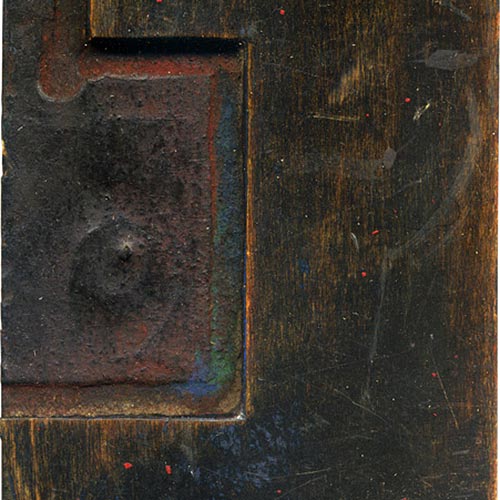

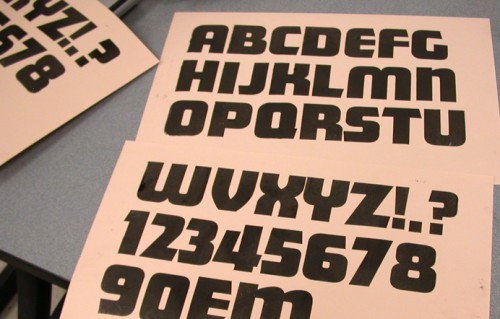

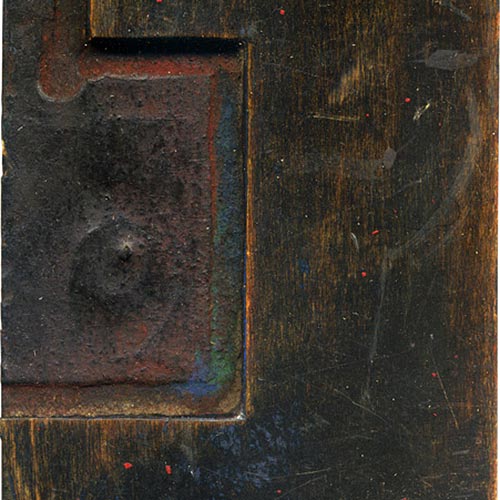

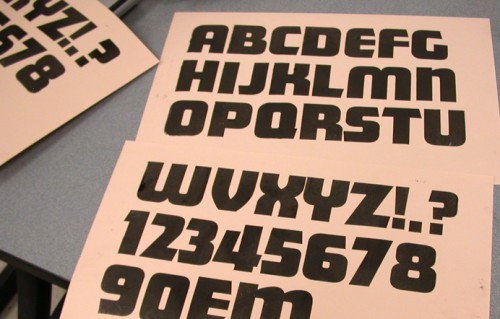

I have been advising Bethany with some of her work on the site so far, which includes several distinct features. First, the Daily Letters and Character Studies series of posts highlight Bethany’s growing collection of type, piece by piece. She provides historical details about the typefaces and manufacturers, but the most prominent and interesting aspect of the write-ups is her attention to the details of each particular block as its own unique object. Her reflections on specific scratch marks, manufacturing irregularities, specks of dried ink, etc often border on archaeological examinations. The posts are appropriately accompanied by high-resolution scans to show all the details.

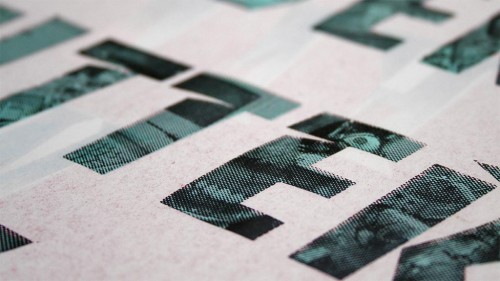

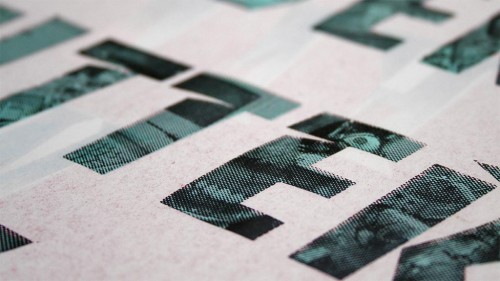

Details from wood type scans at End Grain

Some blocks are also presented side-by-side with their prints for comparison. The prints aren’t necessarily the cleanest proofs possible, but this is partially forgivable considering the limitations of Bethany’s on-press experience so far.

Beyond showing Bethany’s type collection, the site functions as a resource for others interested in letterpress printing, with growing reference info on print shops, websites, retail stores, etc. Relevant content is also aggregated from sites like Flickr, Etsy, eBay, and Twitter.

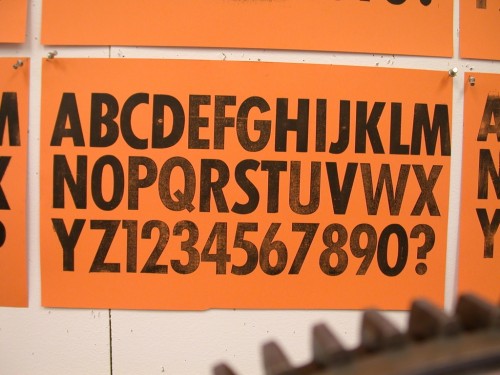

Another element of interest on End Grain is a series of posts documenting Bethany’s experiments with movable type production. The projects so far have ranged in scope from replacing missing characters in an incomplete font, to creating blocks of a digital typeface that hadn’t previously been available as movable type.

Up until now, all of the projects have been executed by affixing thin laser-cut plexiglass to a wooden base, emulating the veneer type production process.

Plexiglass veneer cuts and wooden base blocks for a set of Futura Condensed printing type. Note the guidelines inscribed on the base blocks to assist in aligninment when affixing the veneer cuts.

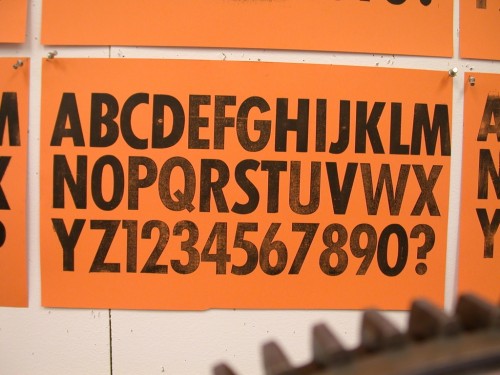

Futura Condensed with plexiglass veneer replacement blocks

Print made with the completed Futura Condensed font

Replica blocks of № 504 made with clear plexiglass

Print made with replica blocks of № 504

Plexiglass veneer blocks of Matinee Gothic

Print made with the Matinee Gothic blocks

These projects on their own are enough to warrant recognition, but the fact that they’re all done by the same student and presented the way they are makes them that much more notable. Furthermore, knowing that Bethany’s printing experience has been relatively limited, it’s impressive that she’s enthusiastic enough to initiate her own projects. This comes as no surprise though, knowing her strong personality and enthusiasm. It’ll be interesting to see what other things she does in the future and beyond graduation.

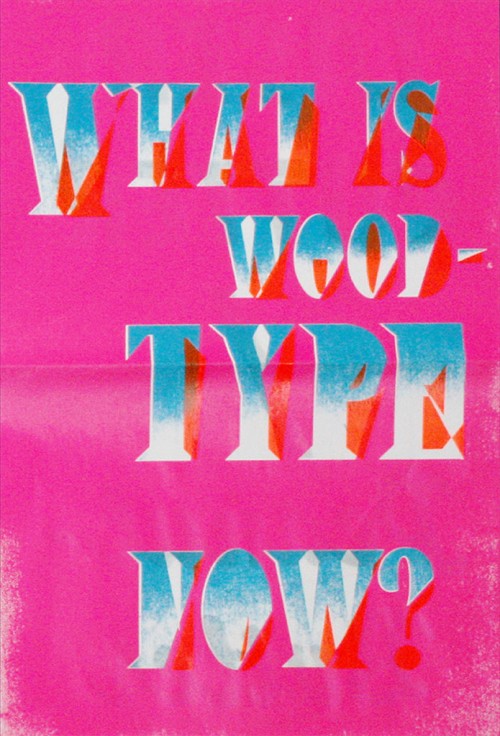

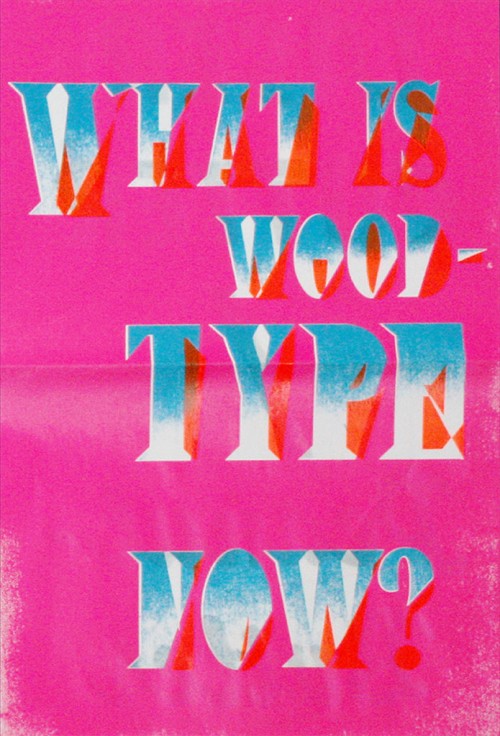

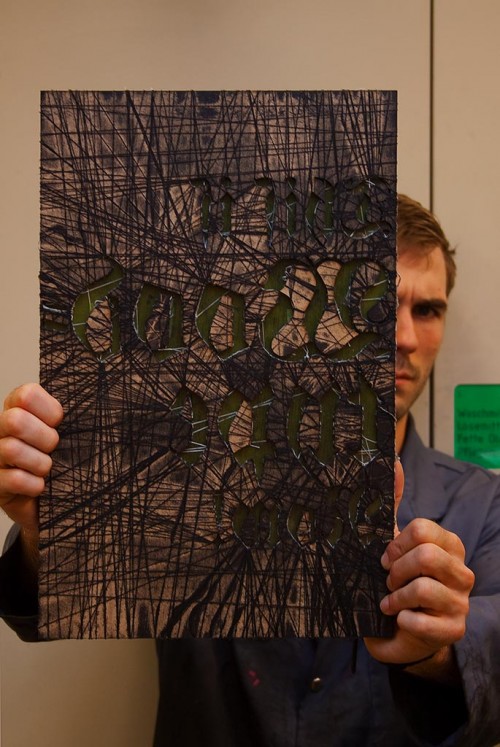

Detail of a poster sheet from the "Woodtype Now!" project by Dafi Kühne

Dafi Kühne at Hatch Show Print in 2008

Dafi Kühne is a designer and printer with a recent bachelor’s degree from the Zurich University of Arts‘ Visual Communications department. He also worked as an intern at the legendary Hatch Show Print poster shop in 2008.

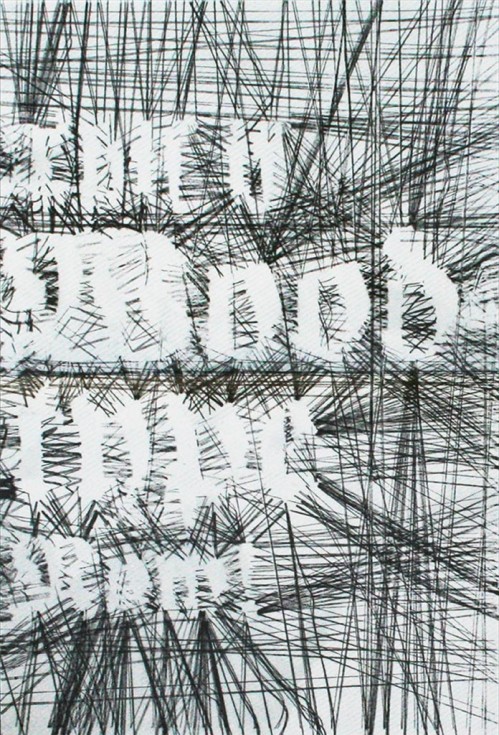

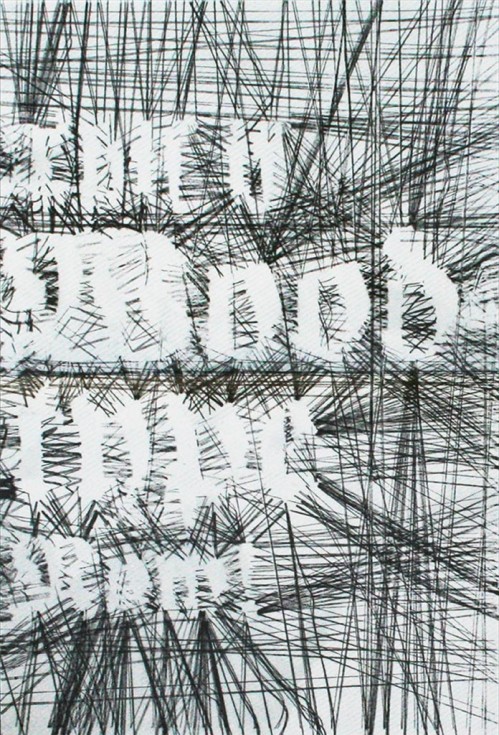

Woodtype Now! is Kühne’s bachelor thesis project that explores experimental production methods for letterpress printing. It is one of the more interesting efforts from a handful of contemporary wood type projects I’ve come across recently, and stands out in its decidedly theoretical approach to the idea of wood type in a modern context…

Wood Type Now! seeks to transform […] traditional mechanical production methods into the 21st century by revolutionizing the way that prints are designed and produced by incorporating new peripheral hardware (i.e. lasercutter). Through the process of exploring the possibilities in regards to materials used and the way the classic printing block and set up are interpreted, the project redefines the conventional boundaries of the subject matter — as opposed to recreating a status quo with new means — and unlocks new frontiers.

Woodtype Now! dissertation

The project, mentored by Prof Rudolf Barmettler and Kurt Eckert, consists of several related parts. First, a 30-page dissertation, Woodtype Now! — An Analysis of Application Range, Possibilities and Potential of Woodtype for Graphic Design in the 21st Century was written under the mentorship of Margarete von Lupin.

Eight interviews were conducted during research for the dissertation. The subjects of the interviews include…

The interview document contains a lot of what Dafi describes as “blah blah”, but there is also some interesting information on the history of European wood type (a topic that has been relatively under-represented in the significant publications to date).

Anyone interested in reading the full dissertation or interview documents are encouraged to contact Dafi directly via e-mail at hello@woodtype-now.ch.

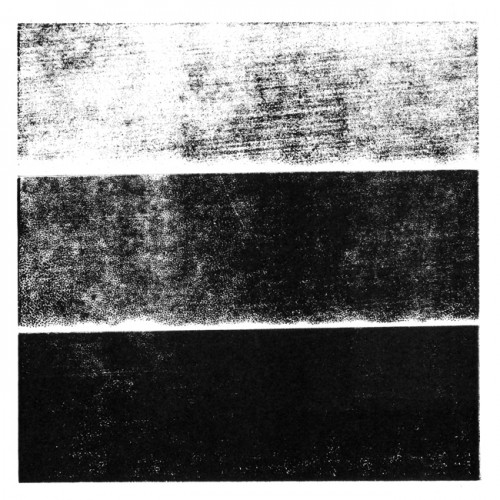

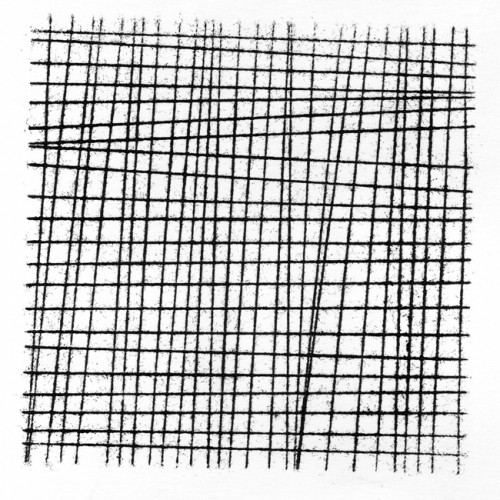

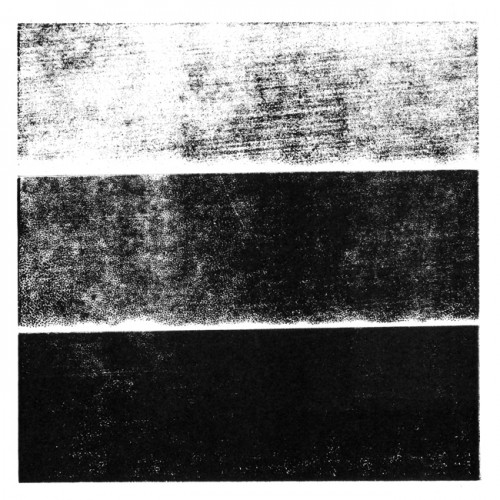

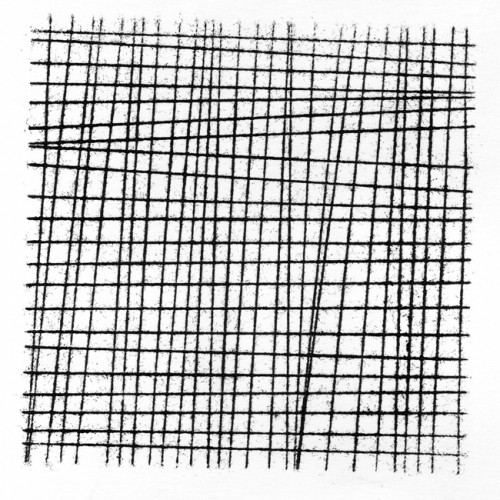

The next aspect of Woodtype Now! is the webpage which presents experimental prints (single-color, 10 cm × 10 cm) using various letterpress production techniques, including lasercutting, “shimming”, adhesive foil application, wrapping with string, etc (selected images shown below; explore the webpage for a more comprehensive overview).

Finally, Dafi produced What is Woodtype Now?, a 9-page, 23-colour letterpress newspaper interpretation/expansion of the experimental exercises (again, only a small sampling is shown here; see the webpage for more).

While none of the material from the Woodtype Now! project is technically even wood type in the strictest sense of the term — it would be more accurately described as “typography printed from composite woodblocks” than proper movable type — Dafi has also done some extensive wood type production leading up to his dissertation. In 2008, he used a lasercutter to produce a full 10-cicero (≈128 pt) wood type veneer font of Univers with 250 individual sorts, as well as some larger sample letters of Railroad Gothic.

When I asked Dafi about the use of composite plates compared to movable type, his thoughts seemed to echo points from the ongoing debate about whether relief printing from digitally conceived photopolymer plates is any more or less valid than using traditional movable type…

[Producing movable type] was an important test before Woodtype Now! because I learned that it isn’t hard to make wood type in a traditional sense. There’s a lot of industrial art and woodworking knowledge involved, but from the present technical point of view, it’s not a big problem with a lasercutter.

More important for me was the question: What is wood type today? What can I do with a lasercutter that you can’t do with a pantograph and router? What do wood type prints look like today, without generating old-school or retro posters? Movable wood type has the huge advantage that it is reusable and it gives the analog layout and design process a boost, but it can’t be produced instantly (even with lasercutting there are two component constructions, so it takes a long time to produce). For Woodtype Now! I needed to do something fast! And now, after this work, I can decide if I want to do something with movable, reusable type or just a single-use woodblock. I can also decide if I want to use sustainable or cheap material … It all just depends on the project.

I believe his logic is mostly valid, and am glad he utilizes the technology as he sees fit, without any dogmatic reservations. I would be interested, however, to see how his experiments with movable type might progress if he were experimenting more with the fundamental concept of how a piece of type can be physically constructed today, potentially altering how it is composed with other pieces of type. Either way, the work he’s accomplished thus far is impressive as is and exists on a conceptual and academic level above most undergraduate design work.

After graduating, Dafi still prints from his personal studio in Zürich. I wouldn’t be surprised to see him on the list of speakers at a future type or printing conference.